An Early Start

on Success

Undergraduate Research Offers Students a

Chance to Delve Deeper

At labs across campus, students peer into beakers in search of scientific discoveries. Others conduct interviews to learn more about how the mind works. Some collect material samples in the field to chart the changes in and challenges to the environment.

Cal Poly Pomona provides ample opportunities for undergraduate research through academic programs, learning communities and senior capstone projects. The aim is to enrich the learning experience for students and ensure their success, says Winny Dong, director of the Office of Undergraduate Research.

“Our mission is to spread the opportunity for undergraduate research to students as early in their career as possible,” says Dong, a chemical and materials engineering professor.

“Participating in research can have a profound impact on a student. We want to engage students in research as early as their freshman year.”

There’s a direct link between research and student success. Undergraduates with research experiences are six times more likely to graduate than their peers who do not, according to an annual campuswide survey.

“We know that undergraduate research has an impact, that it is important to student success,” she says.

Dong formally established the Office of Undergraduate Research in 2013 to host events, manage scholarship programs and assist other groups on campus in providing research opportunities for students.

Here is some of the research that CPP students are conducting and how the projects have bolstered their sense of self and drive to succeed.

“Participating in research can have a profound impact on a student. We want to engage students in research as early as their freshman year.”- Winny Dong, Director of the Office of Undergraduate Research

Representation Matters

The world may classify Costa Rica, Chile, Nicaragua, Haiti, Guyana, Bolivia and Brazil as developing nations, but all are trailblazers in at least one regard.

Each country has elected a woman as president or prime minister.

Brittany Banner, a senior majoring in political science who is a native of Belize, was stunned that a democratic superpower like the United States has not yet elected a woman to its highest office.

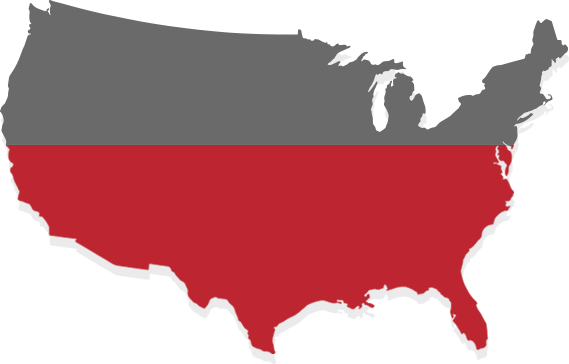

As she began her research on the underrepresentation of women in politics, Banner found that although women comprise more than 50 percent of the country’s population, just over 19 percent of the 435-member House of Representatives is female. The numbers are similarly skewed in the Senate, with just 21 women serving in the 100-member upper chamber of Congress. The government’s judicial branch also is predominantly male, as 33 percent of the state and federal court judges nationwide are female.

Underrepresentation of Women in Politics

of the United States population is women

“It kind of blew my mind,” she says. “It can’t be real. Male legislators don’t really fight for women’s issues. How can we consider the U.S. a democracy if half the population is underrepresented?”

Banner has been interested in women in politics since she took a lower-division political science course several years ago. As part of the Ronald McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, she found a mentor in Political Science Professor Mario Guerrero. The program offers participants a chance to work with a faculty mentor, conduct research in their discipline and prepare for graduate school.

For her research, Banner analyzed how major media outlets such as the Los Angeles Times, New York Times and CNN discuss female and male candidates. She found that discussions about women often veered into talk about hairstyles and clothing, along with juggling motherhood and political life.

“It’s unfair because we don’t ask these questions of male politicians,” she says. “This reduces the number of women even thinking about running for office. Leadership is considered more of a masculine trait. The lack of women running for office exemplifies the theory of how we view leadership.”

Banner, who plans to pursue a master’s degree in education policy and then a doctorate, says that conducting original research has helped her feel more confident.

“You’re able to engage yourself in areas of study you’re interested in,” she says. “They are trusting us to do original research. I am able to say this is my project, and I want to do it my way.”

“They are trusting us to do original research. I am able to say this is my project, and I want to do it my way.”Brittany Banner, senior majoring in political science

Born to Farm

It’s not that Joseph Wolf fears the unknown. He just doesn’t like the mystery.

That is the main reason why Wolf, a senior majoring in plant science, is drawn to research.

“When something is unsolved, it just kind of bothers me,” he says. “With research, you can answer your own questions. To me, it is the only way to answer them objectively and reliably.”

Wolf, who transferred to Cal Poly Pomona from Mt. San Antonio College in 2016, got involved in research right away. He is in both the McNair Scholars and Achieve Scholars programs in the Office of Undergraduate Research. He also is in the OUR GRAD Program, which prepares participants to apply for graduate school through workshops, campus events and involvement in OUR’s bi-annual student conference and symposia.

He aspires to work in restoration ecology, a field that initiates and accelerates the recovery of ecosystems that have been damaged by humans or natural disasters. Both of his research projects are in keeping with his goal of using agricultural land as a method for ecological restoration.

For one project, he is teaming with engineering students to design an affordable drone that farmers can use to monitor their crops by air. The second project involves testing a vacuum attachment for a tractor to potentially eradicate the Bagrada bug, an invasive species that feeds on cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cabbage and has devastated California farms.

“My dad had taught me growing up on the reservation how to survive in the wilderness, but becoming a cowboy and having to live out there for months at a time was tough,” he says. “You find whatever water you can. You learn to hunt for your food. You got three or four hours of sleep because you had to take turns staying up to watch the herd. It wasn’t uncommon for me to be woken up by shotgun because someone was trying to protect the herd.”

One of the ranchers Wolf worked with in Montana suggested he come to California and pursue his education. Wolf says that although Cal Poly Pomona may not have as many resources as research-intensive institutions, the programs on campus are comparable.

“The quality is way above par for not being an R1 university,” he says. “The big reason for that is the people involved. The people who bring quality to a program are the leaders of a program.”

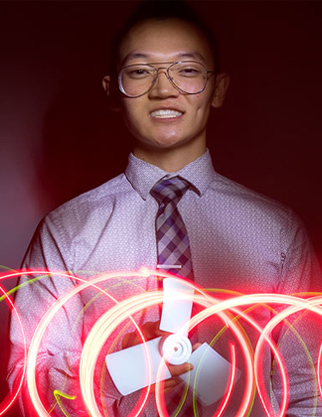

Problem-Solving in Real Time

When Brooke Singleton began doing research as a freshman, she didn’t mind serving as the group’s assistant.

While the upper-division students in the group tested new materials for hip-replacement surgeries, Singleton prepared the test samples, created posters for conference presentations and made their PowerPoints pretty. And she soaked up every word the team discussed, even though she didn’t understand everything being said.

“I started really gaining a good appreciation for the research experience,” she says.

This year, Singleton, a junior majoring in chemical engineering, is heading her own project on fuel cells, a zero-emission source of energy that could replace gasoline.

“The thing about fuel cells is that they work great, but they are not widespread partially because of cost issues,” she says. “We are addressing this issue by developing cost-effective materials.”

Singleton, a student in the Kellogg Honors College who has worked under Professor Ravi Vilupanur, chair of the chemical and materials engineering department, is conducting her research as part of a required project.

Hands-on research has afforded her many opportunities to challenge herself. Last summer, she participated in a joint project conducted by Cal Poly Pomona and Northwestern University. She interns at JPL, testing and preparing materials, and also analyzing data.

She credits her experience at Cal Poly Pomona for opening doors to research and internship opportunities.

“Because I did research here, I was more attractive to other universities who do research,” she says.

“There’s just this exchange of information. One student may know information you don’t know. Others offer insight.”Brooke Singleton, a junior majoring in chemical engineering

The problem-solving skills she is getting from research is something she can apply to her work in the chemical engineering field.

“Nothing goes perfectly in research,” she says. “You have to really scrutinize your data. You have to really doubt but verify. This careful eye I have developed in research will really help me on the industry side.”

A Slow-Burning Activism

Tucked away on a small lot behind a historic church in downtown Upland lies a small community garden that serves as an outdoor classroom.

For Anna Cook, it’s where she conducts research for her senior project. It’s a place that has taught her the value of a sort of quiet activism that links tradition with the now.

Cook, a senior majoring in gender, ethnic and multicultural studies, regularly visits the Chaffey Community Cultural Center’s Tongva Living History Garden to conduct what is called participatory action research, where she actually gets her hands dirty digging in the soil.

“In the midst of school work, it’s very de-stressing,” she says.

She also volunteers in the garden to conduct interviews and collect data.

A year ago, Cook completed a project in her native studies film class on botany and traditional uses for plants. So when she was brainstorming ideas for her senior capstone project, she decided to expand on the topic of indigenous ways of teaching and learning. Professors Charles Sepulveda and Sandy Dixon, interim chair of the ethnic and women’s studies department, connected her with Barbara Drake, a Tongva elder who co-founded the Living History Garden.

Cook says she learned a great deal about decolonization of plant uses and how projects such as the Living History Garden are a way to push back against the notion that the traditions are lost.

“It’s really like a slow-burning activism,” she says. “These traditions are not just stuck in the past. The traditions may have evolved. Things change, and people adapt. Society doesn’t get to decide what being Native American looks like today, whether it’s traditional or modern or a blend of both.”

The next steps in her research project involve adding the findings and conclusions to a mostly written paper that she will present to a group of faculty and students.

Cook says the deep connection to her research project has made learning come alive.

“This is the first time I have been able to delve into something that is super interesting to me,” she says. “This research part has allowed me to go deeper into something of my own choosing. It continues to teach you how much you don’t know. There is always something more to learn if you just kind of keep an open mind. And it pushes you to reflect on your own behavior and actions and take it to the next step.”

Published May 17, 2018