They could have been mistaken for would-be Steven Spielbergs.

In mid-February, 13 Cal Poly Pomona faculty members were each equipped with a webcam, a set of microphones and all the necessary cables, chargers and headsets.

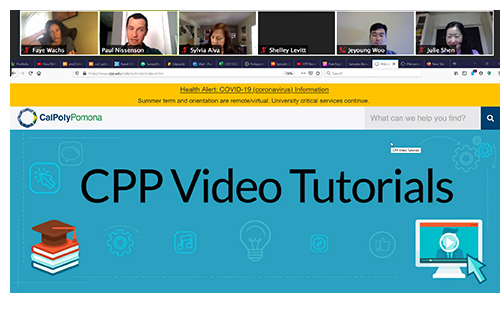

Their assignment: produce high-quality videos that support new ways of teaching and will become the foundation of department-level video libraries open to students, faculty and the general public.

The amateur videographers took part in what’s known as a Faculty Learning Community (FLC), a peer-led group of instructors who join together over a semester in an active, collaborative project. The 13 faculty came from four departments that rarely had a chance to interact: English and modern languages; civil engineering; chemistry and biochemistry; and the University Library.

The amateur videographers took part in what’s known as a Faculty Learning Community (FLC), a peer-led group of instructors who join together over a semester in an active, collaborative project. The 13 faculty came from four departments that rarely had a chance to interact: English and modern languages; civil engineering; chemistry and biochemistry; and the University Library.

“I joined because it’s always a pleasure to meet people across campus, and I really wanted the experience of learning something new, of being a student again,” says Julie Shen, head librarian for references services.

Seema Shah-Fairbank, a civil engineering professor, was eager for tools that would allow her to disrupt higher education’s traditional lecture-based classes.

“I was invigorated by the idea that I could change pedagogy from what I experienced when I went to college and the professor professed for an hour or maybe two,” she says. “Experimenting with new models of teaching really excited me.”

What Shen, Shah-Fairbank and their fellow faculty members could not have predicted was just how vital their new skills would become when midway through the spring semester, the COVID-19 crisis struck and Cal Poly Pomona became a completely virtual campus.

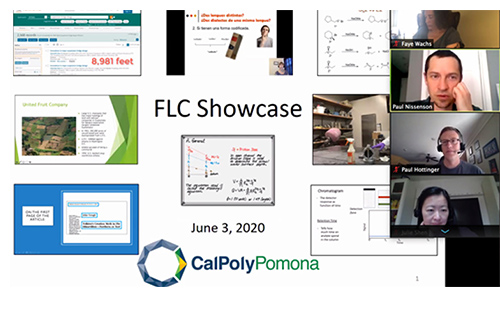

“We’d wanted to seed people in places to become leaders as their departments worked to develop video resources,” says Sociology Professor Faye Wachs, co-principal investigator on the FLC. “With COVID that timeline became very, very compressed.”

Addressing the FLC participants in June, Provost Sylvia A. Alva noted that their leadership had new urgency. “I want to thank each and every one of you for stepping up, for being pioneers and innovators in this very important space,” she said. “You’re on the leading edge, the cutting edge of where we need to move as a campus.

A Virtual Boost to Grades

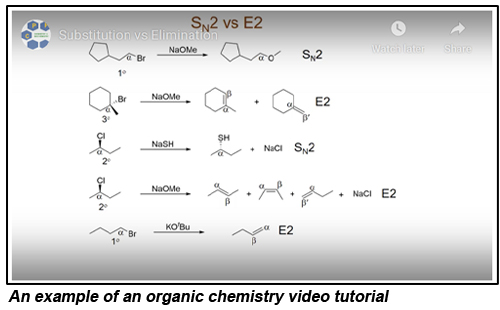

Cal Poly Pomona had solid evidence that video resources could make a dramatic difference in student performance. In an award-winning initiative a few years ago, Mechanical Engineering Professor Paul Nissenson, along with Wachs and Psychology Professor Juliana Fuqua, had redesigned a required and challenging engineering course in fluid mechanics that about one third of students were failing.

Nissenson abandoned the traditional lecture format. In its place he “flipped” the class structure to introduce students to material through videos they would watch in advance, and then devoted classroom time to active learning exercises. Sometimes the class would be divided into teams that competed to solve problems for a prize of candy or extra credit. The result of this fresh approach: the pass rate soared to nearly 90 percent.

What’s more, the mechanical engineering department built its own YouTube channel. Today ME Online has a robust library of more than 600 instructional videos that have, collectively, been viewed nearly 7 million times.

While the videos attract a global audience, a preliminary assessment shows that they’re exceptionally valuable for CPP students.

“Students who were struggling with a class were very appreciative of their ability to view these videos at home,” says Fuqua, “and learn at their own pace.”

Adds Wachs, “One thing that came out of our survey of students is that they want more videos, especially for those difficult bottleneck courses.”

Could the success of the mechanical engineering department be replicated across the campus? That’s what Nissenson as the leader of the FLC, with Wachs and Fuqua as co-principal investigators, set out to explore.

Team Effort

It took a village to turn college professors into skilled videographers. During seven sessions spread over spring semester, a wide swath of campus resources were devoted to training the FLC participants. Victoria Bhavsar, director of the Center for the Advancement of Faculty Excellence (CAFE) and several members of her department, attended every workshop, offering guidance on best practices in video design. Trevor Henderson, director of MediaVision, the university’s on-site audio and visual facility, provided technical support and hosted several workshops. Jason Beers, lead of the web development team, helped create webpage templates for the video tutorials library, along with Richard Feldman, CAFE staff member, who played a major role in getting the website ready. Nine student research assistants aided in gathering and assessing data on the effectiveness of the FLC.

Guest lecturers shared their expertise. Among them was Ann Loomis, associate director of the Disability Resource Center, who gave a presentation on how to make videos accessible for all viewers. One tip: always provide captions for students with hearing issues or for whom English is not their first language.

Other faculty presentations on video and different instructional styles were given by Felicia Friendly-Thomas (psychology), Shokoufeh Mirzaei (industrial and manufacturing engineering) and Jodye Selco (chemistry and biochemistry).

Over the course of the semester, each participant produced four brief video tutorials on subjects that ranged from cost estimating in construction engineering management, open channel hydraulics, creating an annotated bibliography and history of the Spanish language. With each video, the quality soared. (You can view the videos that the FLC participants created at www.cpp.edu/videotutorials.)

Over the course of the semester, each participant produced four brief video tutorials on subjects that ranged from cost estimating in construction engineering management, open channel hydraulics, creating an annotated bibliography and history of the Spanish language. With each video, the quality soared. (You can view the videos that the FLC participants created at www.cpp.edu/videotutorials.)

“By the fourth videos I was just blown away by how much better they’d gotten,” Nissenson says. “And I saw great examples of things I’d never considered doing myself, like throwing in a joke once in a while to make the material more accessible or incorporating a musical soundtrack.”

Peer mentoring was key to this improvement. Participants viewed each other’s videos and offered feedback and tips, like how to improve pacing, or find images, video and audio that could be used without cost on CreativeCommons.org, the search engine of a nonprofit organization that compiles copyright-free content. Sometimes tweaks were made right on the spot.

“People would not only point out there’s a problem with, say, distracting background noise,” says Wachs, “they’d say, ‘here, let me show you how to fix it.’”

Olga Griswold, professor of linguistics, found it especially helpful to hear from instructors outside of her own Department of English & Modern Languages.

“The feedback from colleagues who come from different disciplinary perspectives allowed me to step out of my own little disciplinary ‘box,’ and look at my videos from the outside, more from the students’ perspectives than mine,” she says.

Bhavsar believes that the professional relationships forged across departments were every bit as important as the video skills the participants gained.

“People are better teachers when they have a broader view of the universe,” she says. “The more you know about a lot of different things, the better you’re able to reach the diverse students in your classroom. And one of the best ways to know a lot is to know a lot of people and to be able to talk to different people around the university.”

Next Steps

While no one quite reached the cinematic brilliance of Steven Spielberg, the FLC gave faculty the opportunity to practice using new technology and step out of their comfort zone. Never mind that one fellow FLC participant had told Dragos Andrei, civil engineering professor, that the wheel in his video on pavement fractures looked more like a donut.

“I think we should keep getting together on our own,” he said to his fellow participants at an FLC showcase, “so we can continue going over our videos and sharing advice.”

It was a sentiment that was shared by other participants, as well as by Provost Alva.

“This is a community that needs to continue,” she said. “We’re pivoting to a world with a growing reliance on digital content and you’re beacons of possibility, the light that shows folks, ‘this is hard work, but we can do it.’”

Tips from the FLC: How to Create Videos That Will Have an Impact

- Define your learning objective. Be purposeful about what you want students to know, understand or be able to do after watching the video.

- Keep in mind that students will be watching your videos on all types of devices, including laptops, desktops, tablets and smartphones. Make sure everything, including fonts and images, will work on screens of all sizes.

- Break your topic into smaller “chunks” that can be covered in brief videos of three to five minutes. Instead of trying to reproduce a lecture, present a single, concise and well-organized idea.

- Engage your viewers as active, rather than passive, participants. Give them something to do that reinforces the learning in a meaningful way, such as posing questions, directing them to supplemental reading, asking them to analyze findings or to conduct an exercise or experiment.