The Barioni family knows the feel of soil under their feet.

From a village on the Swiss-Italian border, to a more rural Los Angeles of late 19th century, to the wide-open space of the Imperial Valley – farming has been the family business for five generations.

Don Barioni Sr.’s grandparents, dairy farmers on the Northern Italian border, immigrated to Los Angeles in the 1890s with plans to continue farming in their new homeland. Soon after arriving in Los Angeles, the family moved to San Luis Obispo to set up their farm. The Barionis learned that water from the Colorado River was plentiful and secure for farmers in the Imperial Valley, and in the early 1900s, they headed to the area bordered by San Diego, Mexico and Arizona to grow alfalfa, wheat and grain for dairy cows. The Barionis were one of the pioneering farming families in the Imperial Valley, starting with around 100 acres and eventually growing it to a medium-sized operation of several thousand.

“The river water is still, and will always be, most important,” says Don Barioni Jr., who now heads the operation for his father, who is retired.

Barioni Sr. (’60, agronomy) attended and graduated from Cal Poly Pomona, then worked for a while for Chevron-owned Ortho Chemical and United Fruit before returning to the farm with new ideas to improve the business.

“My dad’s generation was the first to go to college,” says Barioni Jr. “Don Sr. started growing fruits and vegetables. The dollar return per acre was much higher in the produce business compared to growing forage crops in the 1970s and 80s. But you had to be willing to go sit with food company executives, and he could do that with the tools and encouragement he received from attending Cal Poly Pomona. My dad took us into overdrive. My grandfather lost more sleep over my dad taking us into overdrive than my father did. Dad said, ‘I understand the risk versus return.’”

The family also once had thousands of acres of cotton in the 1970s and 80s until the boll weevil, a global price drop, and new technology that made the cotton gin obsolete, he says.

These days, the Barionis still grow some ground crops through their ImperialAg Co. But they now equally rely on their Imperial Plantation Farm & Nursery Co. tree crop business, which has thousands of acres of lemon trees and several hundred acres of date palms for fruit and olives for oil. They emphasize sustainable practices.

Their ownership of the land has given the family flexibility in what they’ve grown over the years, helping them adjust to the unforeseen – including the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Farmers who own their own land are better positioned to weather this pandemic because, if you’re paying rent and can’t grow certain crops, then you can’t pay the rent,” he says. “It’s crazy and scary times for farmers during this pandemic.”

When the pandemic struck, the Barionis had already finished harvesting their tree crops and had shifted from risky fruits and vegetables to more stable forage crops.

“Serendipitously, we were lucky that our tree crop harvests were over,” Barioni Jr. says. “The only thing we are harvesting right now are my father’s and his partners’ contracted sugar beets. That doesn’t go on the store shelves. The beets go to the factory and are turned into white sugar.”

Between now and the fall planting and harvesting season then, Barioni says they will only till and or irrigate the land where they grow their crops, along with some re-development, and let the land rest.

COVID-19 definitely will have an impact on what farmers grow and the distribution of those goods, Barioni says.

“This is going to be a teachable moment for the public about how important food is,” he says. “Maybe people will also realize how important farming and ranching are, and food distribution. People are starting to appreciate those semi-trucks.”

Farmers like the Barionis have fewer issues of employee safety related to the coronavirus, because their workers aren’t close together in the fields. Also, farming and ranching now have a lot of safety programs already in place, Barioni Jr. says.

“You might have one guy on a tractor out by himself in a field,” he says. “Workers are miles out in the rural country irrigating, cultivating or harvesting. The definition of rural is wide open spaces. We already had masks, gloves and protective clothing before in our ongoing safety programs. For us at work farming, there’s little difference.”

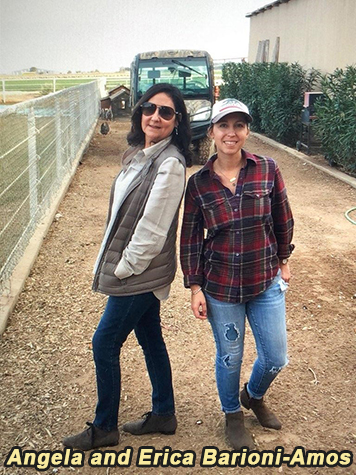

The family also has about 100 acres of olive trees for oil, which are under the watchful eye of the Barioni’s wife, Angela, and daughter, Erica Barioni-Amos, and they own the Imperial California Olive Mill for processing the fruit to bottle for retail.

Barioni-Amos studied interior design and architecture in college, but it is the branding courses she took that have been the most useful in the business. As the director of marketing and administration, she began branding the retail packages for olive oil, balsamic vinegars and table olives.

Also, Erica developed relationships with companies to provide a complementary pantry line of products, such as barbecue sauce and hot pepper jellies.

“I had hoped that I would still have some sort of connection in the family business, but I didn’t know where. The cards were never off the table,” she says. “Growing up, it was a part of me. I take pride in the fact that my family is in the farming industry.”

While Barioni Sr. helped to modernize the operation for the 70s and 80s, Barioni Jr. has introduced the technology of today. He put micro-sensors in the fields to track soil salt conditions and irrigation levels and send that data to the office computer for analysis and monitoring.

Because Barioni Jr. has so many irons in the fire — including a consulting business, a real estate development firm, a company that develops environmentally-friendly and organic pest control products for plants, and his service on the boards of the Imperial County Farm Bureau and Imperial Valley Economic Development Corp. — he has recruited a member of his dad’s Bronco family to help run the farming operations.

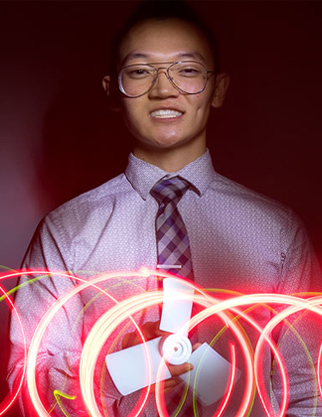

The farm’s operations manager, Alejandro Valdovinos, checks the data and sensor readings to make sure the crops are maintained. Valdovinos (’19, plant science) also oversees facilities, employee and food safety, and labeling, among other duties.

The Coachella Valley native’s father was a labor contractor in the farming industry for more than 30 years. Valdovinos initially started on his father’s path in studying agribusiness but switched majors after taking a couple of plant science classes.

During his last semester at Cal Poly Pomona, Valdovinos interned with Helena Agri-Enterprises at their Thermal, California, branch, which allowed him to get out and meet farmers. He met Barioni Jr. and was impressed with their operation and how hard the family works, Valdovinos says. They bonded over their shared love of date trees, and Valdovinos talked about what he wanted to do after graduation. He was hired.

“For me to get the knowledge that I got at Cal Poly Pomona and be able to come here and try to improve farming is such a blessing,” Valdovinos says. “This is what my family lives for. The only thing we know how to do is be around farming. This is something I see myself doing for the rest of my life.”

Valdovinos agrees with the Barionis saying that “the best fertilizer is your shadow on the land.”

Barioni Jr. hopes the family will continue to cast a shadow on the land for generations to come and keep building on the business, he says.

“I hope the recent changes to our legacy crops — permanent lemon and olive trees, as well as date palms — along with the processing of value-added packages like bottling olive oil for retail, allow the newer generations to have a place to participate in processing, packaging and marketing, something beyond just growing crops in the field.”