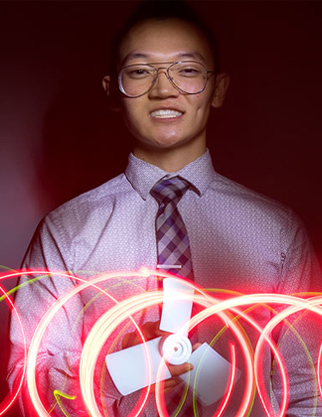

The Forensic Architect

Trained to Construct Buildings, Alumnus Bruce Arita Now Deconstructs Them

Bruce Arita’s job description reads like a Marvel movie meets an episode of CSI.

Anywhere in the world a natural disaster strikes, he’s there. He runs toward burning buildings and investigates the cause of catastrophes.

Where Arita and Spider-Man diverge is their knowledge of architecture.

Arita (’77, architecture) began his career constructing buildings. Then he decided to start saving them. In architecture terms, he shifted his career 10 degrees.

While designing buildings for the first 15 years of his career, construction jobs were abundant when times were good. But when the economy lagged, building projects dried up, leaving him without a job or requiring him to lay off his employees. By the time he endured a third recession, he knew it would be his last as an architect. The traditional kind of architect, at least.

For the past three decades, deconstructing damaged buildings is how Arita has avoided the boom-and-bust nature of his line of work.

His career follows the path of earthquakes, hurricanes, fires and floods. He walks into the ruins of buildings to determine what can be saved and what can’t. It’s called forensic architecture.

“It’s actually much more satisfying than building a new building,” says Arita, the senior vice president and property loss consulting practice leader at Thornton Tomasetti. “We’re trying to save something, a precious building that has a history and all the baggage that comes with that. But not all architects like to walk into a burned out building. It takes a certain type of person to want to do that.”

Though his area of expertise is a highly specialized version of architecture, it requires Arita to wear many hats.

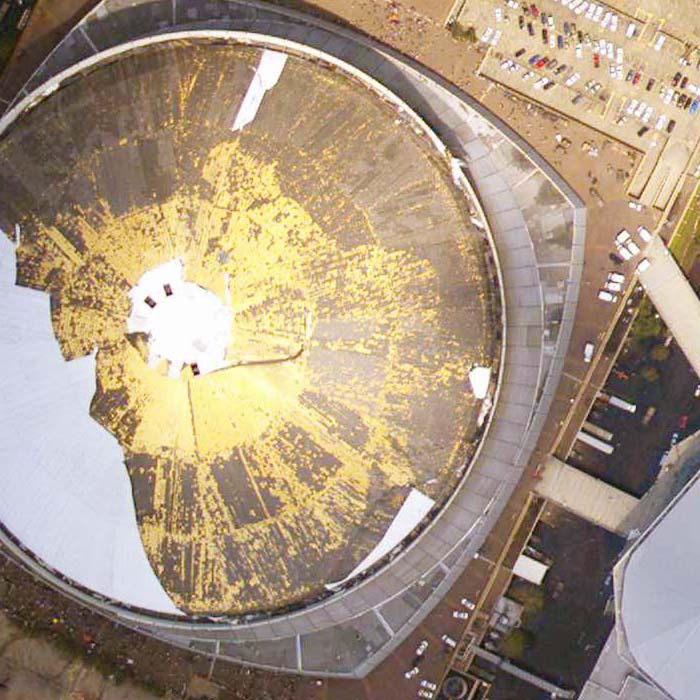

One minute, he is an analyst using a drone to evaluate whether his team can enter a damaged high-rise. The next he’s a crime-scene investigator determining whether a fire was arson. He often works with insurance companies, requiring him to decipher what damage is covered in the fine print of a building’s insurance policy. Much of Arita’s work is confidential given its sensitive nature.

“What Bruce does has a CSI feel to it,” says Jon Lundstrom, an architecture classmate of Arita’s at Cal Poly Pomona who owns his own firm. “We need to know how these things happen and how to prevent them in the future, and Bruce is innovative in the way he goes about doing that.”

What Bruce does has a CSI feel to it.Jon Lundstrom

Though Arita, 63, has saved buildings from London to New Zealand, there may be no greater sentiment around the world for a building he has worked on than the One World Trade Center in New York City.

The iconic skyscraper, which replaced the Twin Towers destroyed on Sept. 11, 2001, in the deadliest terrorist attack in U.S. history, sustained its own share of severe damage.

In 2012, before construction was even complete, floodwater from Superstorm Sandy gutted the basement of One World Trade Center. The storm that killed 149 people and caused $20 billion worth of damage across the Northeast swamped the basement of the building with water — enough to fill the L.A. Rams’ new football stadium in Inglewood.

Arita’s firm was charged with saving not just a building, but a symbol of healing and restoration from 9/11. When a natural disaster battered a monument to New York City’s most trying time, the physical damage was rivaled by the emotional wound.

“There was still a lot of pain from 9/11,” Arita says. “There was a museum with a lot of artifacts from 9/11 that were compromised in that basement. It was very emotional for a lot of people to deal with.”

Of his myriad projects around the world, Arita says One World Trade Center remains the most satisfying because of what its restoration symbolized to New York City and the country.

He gravitated toward disaster because of the appreciation he felt after surviving each trying experience of his own career, whether it was riding the economic roller coaster during his early days as a conventional architect or pulling all-nighters to propel himself through architecture school at Cal Poly Pomona.

Artita’s preparation for a career wading through largely uncharted territory – each natural disaster leaves its own unique problems behind – began when he was forging his own path through college. The difficulties, he says, prepared him for everything.

“They were tough years. Good, tough years,” Arita says. “When somebody is saying ‘I’m having a hard time,’ I tell them to enjoy it. That’s what prepares you to be successful.

“The academic experience is great, but you need to have the friction and corrosion that go with real life that makes that education much more tangible. When I got out of Cal Poly Pomona, I was ready for anything.”

I’m never going to run out of work.Bruce Arita

Published May 17, 2018