Battle

Scars

Veterans Resource Center helps former Marine heal and find a sense of place

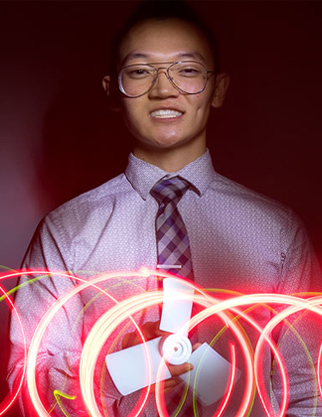

A permanent crease between his brows tells the story of who Larry James Martin used to be.

The ready smile, his effortless ability to make friends and his propensity for dropping pearls of wisdom speak to who Martin is now – a man anchored by his faith, dedicated to his wife and two children and passionate about the fellow student veterans at Cal Poly Pomona he sees as extended family.

It’s a place where you can come and be yourself.”

A rough childhood, teenage rebellion and four years of serving in the U.S. Marines — including combat stints in Afghanistan and Iraq — kept him angry at the world and scowling all of the time.

“Hate scars you,” says the senior majoring in geology. “If you don’t let it go and release that stuff, it will eat you up.”

Martin has learned to let go, and while keeping his aggression in check remains a work in progress some days, he has grown in the past few years. He credits some of that growth to Cal Poly Pomona, particularly his connection to the Veterans Resource Center on campus.

“It’s a place where you can come and be yourself,” Martin says of the center. “People understand you. It’s given me that family that I needed to keep going and keep succeeding.”

“BLOWN, THROWN AND TWISTED”

The path to success was not always a smooth one for Martin, who grew up in the small town of Andrews in what he calls “the great country of Texas.” His mother left when he was 6. Four years later, his father married “a sweet woman” from Mexico who taught him to speak Spanish fluently. However, Martin’s dad struggled with substance abuse. Angered by his father’s addiction, Martin left home at 17 and spent two years homeless and couch surfing.

When he was 19, Martin moved in with his uncle in Oklahoma City. He sold furniture at Big Lots in the mornings and worked construction in the afternoons. In the evenings, he taught ballroom dance at his uncle’s studio Dance Magic — cha cha, meringue and rhumba among others.

“Sometimes when the kids are asleep, I will turn on music and my wife and I will dance,” he says. “They say if you don’t use it, you lose it.”

After a while, Martin grew restless in Oklahoma City and moved back to Texas.

In 2005 and at age 20, he went to the mall to find a job and saw a U.S. Marines sign at a recruiting center. Just as he spotted the neon sign, it burned out. For Martin, that was a sign of a different sort. Inside the office, he saw photos of bombs and Marines in battle. He thought of his maternal and paternal grandfathers, who had served their country proudly, and he decided to join up.

He was in Iraq’s Al Anbar Province in 2007. He came home and then returned to Helmand Province in Afghanistan.

“It went crazy,” he says. “There were heavy battles.”

Martin served in a mobile assault unit during his first deployment and in rifle companies during his second. He saw death and destruction up close, and felt the reward of fighting to make things better rubbing against the frustration of changes in the military. He finished his service stationed in 29 Palms. After he was discharged, he worked for a private defense contractor.

While on leave just before his discharge, he met his wife of seven years, Lizzette, on the dance floor at a U.S. Marine Corps ball. They lived six hours apart at that time, but he would make the drive every other weekend to see her. Soon after, he became a father for the first time.

After leaving the military, Martin battled with his demons. His unit has the highest suicide rate of any other, he says, and friends often called late at night to tell him about the suicides of brothers he served with, including his best friend. The first five years of his marriage were punctuated by arguments fueled by alcohol and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Hate scars you. If you don’t let it go and release that stuff, it will eat you up.”

He found God in all of the chaos, and that helped to temper his rage some. He grew kinder.

Martin, who was living in the Inland Empire at the time, attended Mt. San Antonio College but felt disconnected from his classmates who had not been in the military. When classroom discussions turned to the two wars he had fought in, the way some students spoke against the conflicts agitated him.

“I wasn’t ready for college,” Martin says. “I felt aggressive toward the younger students.”

He took a job in construction, but the work was taxing physically.

“I had been blown, thrown and twisted,” he says. “My body was worn out.”

PLAYING THE CARDS DEALT

After community college, Martin attended the University of Phoenix, an online for-profit college, but felt disconnected in a different way. Once, he received a chemistry experiment by mail from his professor with the expectation that he would conduct it at home with no supervision or assistance.

A counselor at the Veterans Administration suggested he apply to nearby Cal Poly Pomona. When Martin visited campus and saw the statue of a Bronco in Bronco Commons, he took that as another sign, because his high school mascot was a Mustang.

The university environment was a culture shock, but Martin found his stride when he got involved with the Veterans Resource Center a couple of years ago.

With his frenetic energy, boyish charm and personality as big as his home state, he made an immediate impression on Elke Azpeitia (’07, philosophy; ’11, master’s in public administration), the center’s veterans service coordinator. She remembered meeting him when he came to campus for a pre-admissions counseling appointment.

“And I did not forget Larry,” Azpeitia says. “That was the first, but not the last time I saw him.”

The two connected and have a strong bond where they can communicate openly and honestly. When Martin’s stress level climbs and he gets frustrated, Azpeitia knows how to calm him.

“The Veterans Resource Center for a student like Larry means a second home,” Azpeitia says. “He came to CPP not having that community. Larry was interesting because he allowed for a deeper relationship to be created. He is one of those who wanted to have that community for the vets.”

Martin has become a very important part of the center, which is celebrating its fifth anniversary this year and serves about 200 students annually. Many student veterans don’t want to be labeled as a veteran, so Martin’s outgoing and approachable style helps draw them in, Azpeitia says.

“I don’t think the Veterans Resource Center would have been as significant without Larry,” she says. “Larry has been our outreach person. He is the most friendly person in the vets center I could have hired. He will go out and do public relations for that veterans center like no one else. To me, that’s invaluable.”

Not only did the center help Martin learn more about services available to veterans and get tapped into financial aid, but it also gave him a sense of purpose on campus.

“I discovered that I had a gift for finding other vets who had never been to the VRC before,” says Martin, who started as a volunteer ambassador for the center and later took a job as an advisor. “I can just tell. It’s in the way they move. Your body speaks a certain language.”

During a recent morning, students pack the Veterans Resource Center, staring at computer screens or chatting around a table in the middle of the room. The conversation flows from the proposed naming of a new betta fish at the center to their lunch plans to an upcoming fitness challenge.

Martin pours himself a coffee, then dumps six packets of sugar into his cup.

I discovered that I had a gift for finding other vets who had never been to the VRC before”

“High energy and very active.” That’s how Alejandro Navarro, a fellow Marine and the center’s lead veterans resource advisor, describes Martin. The two met three years ago at the center and both help their fellow veterans get adjusted to campus life and find the resources they need.

“He is always keeping himself busy doing something,” says Navarro, a chemical engineering senior who served for nine years. “He’s great with people, making people feel welcome.”

This past year, Martin took a couple of quarters off from the center to focus on himself and his family. Forging a deeper connection with his wife has contributed to his growth and made him a better person, he says. Now he is back at the center and excited about his final quarter on campus.

Looking back at his three years at Cal Poly Pomona, Martin says the center has allowed him to give back. He’s learned that the hand a person is dealt in life doesn’t matter. As long as there are cards to play, that’s a winning hand, he says.

“I don’t regret the fighting. I don’t regret the loss of life. I don’t regret the pain and misery,” he says. “It benefited my heart. It changed me from bitter to kind. You understand what humanity is.”

Published October 4, 2017